In the late 1970s, the Episcopal Ad Project began releasing spots taking shots at television preachers and other trends in American evangelicalism.

One image showed a television serving as an altar, holding a priest's stole, a chalice and plate of Eucharistic hosts. The headline asked: "With all due regard to TV Christianity, have you ever seen a Sony that gives Holy Communion?"

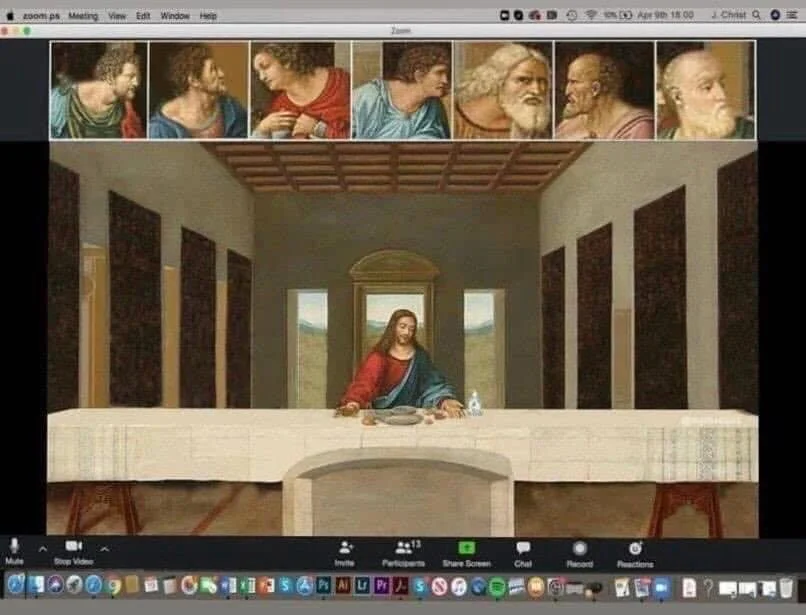

Now some Anglicans are debating whether it's valid -- during the coronavirus crisis -- to celebrate "virtual Eucharists," with computers linking priests at altars and communicants with their own bread and wine at home.

In a recent House of Bishops meeting -- online, of course -- Episcopal Church leaders backed away from allowing what many call "Virtual Holy Eucharist."

Episcopal News Service said bishops met in private small groups to discuss if it's "theologically sound to allow Episcopalians to gather separately and receive Communion that has been consecrated by a priest remotely during an online service."

Experiments had already begun, in some Zip codes. In April, Bishop Jacob Owensby of the Diocese of Western Louisiana encouraged such rites among "Priests who have the technical know-how, the equipment and the inclination" to proceed.

People at home, he wrote, will "provide for themselves bread and wine (bread alone is also permissible) and place it on a table in front of them. The priest's consecration of elements in front of her or him extends to the bread and wine in each … household. The people will consume the consecrated elements."

Days later, after consulting with America's presiding bishop," Bishop Owensby rescinded those instructions. "I understand that virtual consecration of elements at a physical or geographical distance from the Altar exceeds the recognized bounds set by our rubrics and inscribed in our theology of the Eucharist," he wrote.

However, similar debates were already taking place among other Anglicans. In Australia, for example, Archbishop Glenn Davies of Sydney urged priests to be creative during this pandemic, while churches were being forced to shut their doors.

During a live-streamed rite, he wrote, parishioners "could participate in their own homes via the internet consuming their own bread and wine, in accordance with our Lord's command."