In the summer of 2016, two White House staffers – Brian Mosteller and Joe Mahshie – tied the knot in a rite led by one of America's most prominent Catholics.

The officiant was Vice President Joe Biden, who later proclaimed on Twitter: "Proud to marry Brian and Joe at my house. Couldn't be happier … two great guys."

Leaders of familiar Catholic armies then debated whether Biden's actions attacked this Catholic Catechism teaching: "The marriage covenant, by which a man and a woman form with each other an intimate communion of life and love, has been founded and endowed with its own special laws by the Creator. … Christ the Lord raised marriage between the baptized to the dignity of a sacrament."

Conflicts between bishops, clergy and laity will loom in the background as Biden seeks to become America's second Catholic president. Combatants will be returning to territory explored in a famous 1984 address by the late Gov. Mario Cuomo of New York, entitled "Religious Belief and Public Morality."

Speaking at the University of Notre Dame, he said: "As a Catholic, I have accepted certain answers as the right ones for myself and my family, and because I have, they have influenced me in special ways, as Matilda's husband, as a father of five children, as a son who stood next to his own father's death bed trying to decide if the tubes and needles no longer served a purpose.

"As a governor, however, I am involved in defining policies that determine other people's rights in these same areas of life and death. Abortion is one of these issues, and while it is one issue among many, it is one of the most controversial and affects me in a special way as a Catholic public official."

It would be wrong to make abortion policies the "exclusive litmus test of Catholic loyalty," he said. After all, the "Catholic church has come of age in America" and it's time for bishops to recognize that Catholic politicians have to be realistic negotiators in a pluralistic land.

Christian icons and art before the rise of the blue-eyed Jesus with blond hair

For modern skeptics, the 6th-century icon hanging in the Orthodox monastery in the shadow of Mount Sinai is simply a 33-by-18-inch board covered in bees wax and colored pigments.

For believers, this Christ Pantocrator ("ruler of all") icon is the most famous image of Jesus in the world, because the remote Sinai Peninsula location of St. Catherine's Monastery allowed it to survive the Byzantine iconoclasm era. The icon shows Jesus – with a beard and long hair – raising his right hand in blessing, while holding a golden book of the Gospels.

This Jesus does not have blond hair and blue eyes. "Christ of Sinai" shows the face of a wise teacher from ancient Palestine.

"When you talk about ancient icons, you are basically talking about images of Jesus with long hair, a beard and some kind of Roman toga. That's just about all you can say," said Jonathan Pageau of Quebec, an Eastern Orthodox artist and commentator on sacred symbols.

In the early church, he added, believers "didn't ask other questions – about race and culture – because those were not the important questions in those days. … Once you start politicizing icons there's just no way out of those arguments. You get into politics and dividing people and then you're lost."

In these troubled times, said Pageau, many analysts are "projecting valid concerns about racism and Europe's history of colonization and the plight of African-Americans back into issues of church history and art that are centuries and centuries old. It's a kind of category error and everything gets mixed up."

But that's what happened when debates about some #BlackLivesMatters activists toppling Confederate memorials – along with attacks on Catholic statues and even insufficiently "woke" Founding Fathers – veered into #WhiteJesus territory.

"Yes, I think the statues of the white European they claim is Jesus should also come down. They are a form of white supremacy," tweeted Shaun King, author of "Make Change: How to Fight Injustice, Dismantle Systemic Oppression, and Own Our Future."

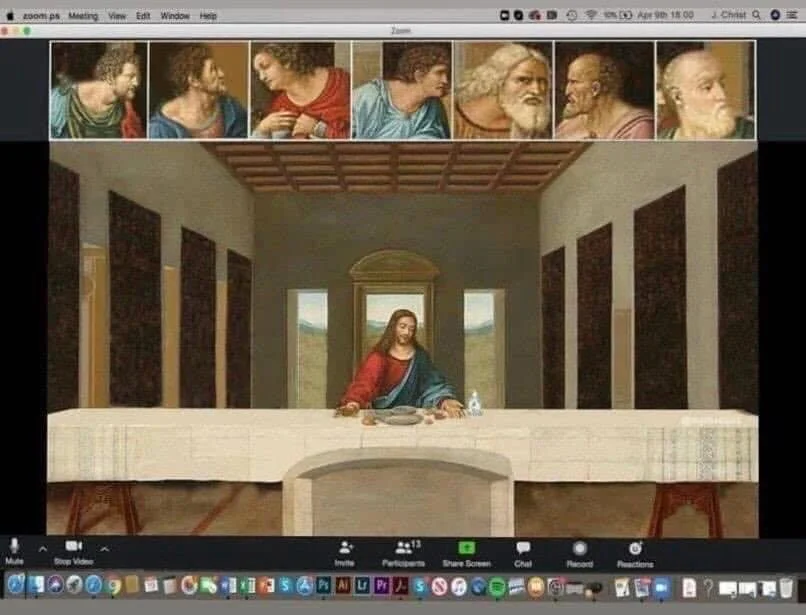

Anglican debate in 2020 crisis: Can clergy consecrate bread and wine over the Internet?

In the late 1970s, the Episcopal Ad Project began releasing spots taking shots at television preachers and other trends in American evangelicalism.

One image showed a television serving as an altar, holding a priest's stole, a chalice and plate of Eucharistic hosts. The headline asked: "With all due regard to TV Christianity, have you ever seen a Sony that gives Holy Communion?"

Now some Anglicans are debating whether it's valid – during the coronavirus crisis – to celebrate "virtual Eucharists," with computers linking priests at altars and communicants with their own bread and wine at home.

In a recent House of Bishops meeting – online, of course – Episcopal Church leaders backed away from allowing what many call "Virtual Holy Eucharist."

Episcopal News Service said bishops met in private small groups to discuss if it's "theologically sound to allow Episcopalians to gather separately and receive Communion that has been consecrated by a priest remotely during an online service."

Experiments had already begun, in some Zip codes. In April, Bishop Jacob Owensby of the Diocese of Western Louisiana encouraged such rites among "Priests who have the technical know-how, the equipment and the inclination" to proceed.

People at home, he wrote, will "provide for themselves bread and wine (bread alone is also permissible) and place it on a table in front of them. The priest's consecration of elements in front of her or him extends to the bread and wine in each … household. The people will consume the consecrated elements."

Days later, after consulting with America's presiding bishop," Bishop Owensby rescinded those instructions. "I understand that virtual consecration of elements at a physical or geographical distance from the Altar exceeds the recognized bounds set by our rubrics and inscribed in our theology of the Eucharist," he wrote.

However, similar debates were already taking place among other Anglicans. In Australia, for example, Archbishop Glenn Davies of Sydney urged priests to be creative during this pandemic, while churches were being forced to shut their doors.

During a live-streamed rite, he wrote, parishioners "could participate in their own homes via the internet consuming their own bread and wine, in accordance with our Lord's command."

Cornel West and Robert George keep asking believers – left and right – to be tolerant

America is so divided that 50% of "strong liberals" say they would fire business executives who donate money to reelect President Donald Trump.

Then again, 36% of "strong conservatives" would fire executives who donate to Democrat Joe Biden's campaign.

This venom has side effects. Thus, 62% of Americans say they fear discussing their political beliefs with others, according to a national poll by the Cato Institute and the global research firm YouGov. A third of those polled thought their convictions could cost them jobs.

That's the context for the efforts of Cornel West of Harvard University and Princeton's Robert George to defend tolerant, constructive debates in the public square. West is a black Baptist liberal and George is a white Catholic conservative.

"We need the honesty and courage not to compromise our beliefs or go silent on them out of a desire to be accepted, or out of fear of being ostracized, excluded or canceled," they wrote, in a recent Boston Globe commentary.

"We need the honesty and courage to recognize and acknowledge that there are reasonable people of good will who do not share even some of our deepest, most cherished beliefs. … We need the honesty and courage to treat decent and honest people with whom we disagree – even on the most consequential questions – as partners in truth-seeking and fellow citizens, … not as enemies to be destroyed. And we must always respect and protect their human rights and civil liberties."

They closed with an appeal to Trump and Biden, reminding them that "victories can be pyrrhic, destroying the very thing for which the combatants struggle. When that thing is our precious American experiment in ordered liberty and republican democracy, its destruction would be a tragedy beyond all human powers of reckoning."

It's distressing that this essay didn't inspire debates in social-media and the embattled opinion pages of American newspapers, noted Elizabeth Scalia, editor at large of Word on Fire, a Catholic apologetics ministry. After all, West and George are influential thinkers with clout inside the D.C. Beltway and they spoke out during a hurricane of anger and violence – literal and verbal – in American life.